Our news is so full of people who do all they can to attack, belittle and tear down that I’ve decided to dedicate the next few posts to people who stand up, confront wrong, build up, heal, and comfort – people who live by their beliefs in spite of all the garbage, violence and trash that is heaped on them. This is the first installment, and my hero is Clarence Jordan.

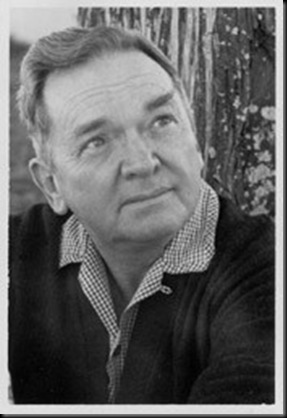

Clarence Jordan was born in Talbottom, Georgia in 1912, and died suddenly of a heart attack at age 59 in 1969.

Clarence Jordan lived what he believed, and he believed in living Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, binding oneself to the equality of all persons, rejecting violence, ecological stewardship, and common ownership of possessions. In 1942 he and his wife moved to a 440 acre farm near Americus, George, calling it “Koinonia”, a Greek work that means fellowship.

Until the advent of the civil rights movement, their neighbors generally left them to live and farm in peace; then Koinonia became the target of a stifling economic boycott and repeated violence, including several bombings.

I met Clarence Jordan at a conference for Baptist ministers in a Chicago suburb in 1963, where he spoke about the civil rights movement and the response (or lack of) of the White churches in the South. A Bible scholar, we were eager to hear what he had to say about the civil rights movement that some claimed was “tearing our nation apart”. Interesting how discomfort turns reality around: It wasn’t racism that was tearing our nation apart, it was opposition to it.

In his quiet, red clay south Georgia drawl, Clarence Jordan said it. The churches, both large and well-known and tiny and unknown, had turned Blacks and their supporters away and in so doing, turned their backs on everything that Jesus taught and stood for. He said it quietly, eloquently and pointedly.

By the end of his first presentation, there was a lot of discomfort in that room. When we returned from lunch, with all of the local Church bigwigs seated behind us, he began by saying that they had asked him to apologize for saying what he had said about the churches negative response to the civil rights movement.

With each of the bigwigs looking pleased, he began his apology. And with each word he spoke, the white faces seated behind him turned to scarlet. I don’t recall Clarence Jordan’s apology other than to say that it turned their words back on them as a scathing indictment. All delivered in his quiet broad red-clay Georgia drawl.

It was brilliant, it was deserved, and I was happy that I wasn’t on its receiving end. It, and the man who delivered it, stand as beacons to me of heroic living.

So I give you Clarence Jordan, one of my heroes, as a life to be emulated.

Among other writings, Clarence Jordan was the author of the Cotton Patch translation of the New Testament. Here is a sample, from his translation of Paul’s letter to Ephesians, which he translates as “The Letter to the Christians in Birmingham.” You’ll see why the church bigwigs at that conference were so uptight:(from Ephesians 11-13):

"So then, always remember that previously you Negroes, who sometimes are even called "niggers" by thoughtless white church members, were at one time outside the Christian fellowship, denied your rights as fellow believers, and treated as though the gospel didn’t apply to you, hopeless and God-forsaken in the eyes of the world. Now, however, because of Christ’s supreme sacrifice, you who once were so segregated are warmly welcomed into the Christian fellowship."

Hard to misunderstand, isn’t it?

That’s all for this post,

Toasty

No comments:

Post a Comment